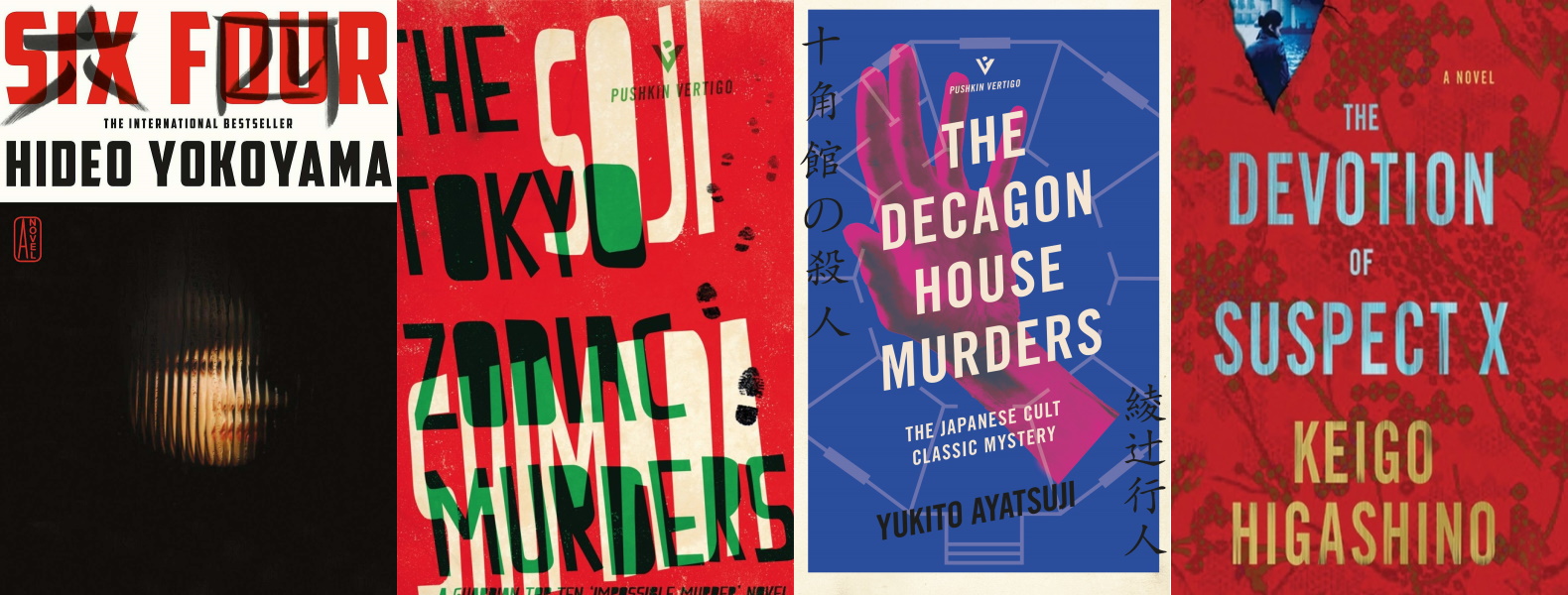

Japan has a long and rich history in the mystery genre, stretching back in particular to the inimitable Edogawa Rampo. I read a few modern classics and although they are not all hits — I was not a fan of Newcomer, for instance — these four I think deserve individual recognition and juxtaposition.

Six Four, by Hideo Yokoyama, was a sensation of a novel when it came out in 2012, and made into a film that was likewise well received. I thought it was an interesting and unusual book in that the main character, originally a detective, is sort of deprived of all his detectorial tools and really doesn’t even know what mystery it is he is attempting to solve.

The main character is the local police department’s press director and is primarily concerned with pacifying reporters, but in doing so he brushes up against several interconnected mysteries and dramas. This isn’t about finding the evidence of murder stashed behind a hidden panel, or tricking the perpetrator into a confession. It’s about a guy trying to do his job and finding that he can’t do it properly without being something of a detective.

Critics of the (quite long) book rightly point out that there’s a lot of detail on the internal organization and conflicts between parts of a police organization that are probably unfamiliar to U.S. readers. Not all of it even pans out, so in retrospect you think, “that whole part was for nothing?” — but that’s the case with every mystery, it’s sort of like an administrative red herring. Turns out that suspicious character really is just bad at their job.

What turns out to be the central drama and conflict takes a really interesting turn towards the end of the book, one that accomplishes that sought-after feeling of other parts clicking into place. The difficulty is that much of the book is quite dry: lots of phone calls, arguments, driving around… and absolutely loads of lighting cigarettes. But the unique perspective was appreciated and ultimately I think it was worth the time I put into it.

The Tokyo Zodiac Murders is a famous piece of work now, a genuine modern classic put out in 1982 by Shimada Soji. It’s a reimagining of the formal Japanese honkaku mystery, a term which means “orthodox” (as Soji himself translates it in an interesting introduction to the Decagon House Murders) and involves, essentially, fair storytelling. In a honkaku book, the writer must present enough information that the reader can solve the mystery themselves with no leaps of logic or last-minute revelations.

The style fell out of favor after the ’50s, as more character, narrative, and culture-focused mysteries gained popularity. Shimada’s Tokyo Zodiac Murders revived the genre in a big way with an ingenious plot and horrifying crimes. Essentially an unsolved mystery from long ago is unearthed by a couple amateurs and the evidence raked over for clues: a mass murder of a whole family, chopped to pieces and buried throughout the country. It’s sufficiently gruesome and no detail is spared, though there is no moment-by-moment recounting of this long-past crime.

As the plot progresses, the evidence piles up until at one point the narrative breaks off and the author addresses the reader directly, saying that as of this moment they now have all the evidence they need to solve the mystery. It’s a challenge, and also an assertion that Shimada has been playing fair: technically, if you were an investigative mind like that of the young detective character, you might be able to figure it out.

It’s far more likely, however, that you will (as I did) think about it for a few minutes and come up empty-headed, then keep reading. Shimada actually interrupts again, as I remember, basically saying “now you have a few extra clues… think about it. If you can’t get it, read on.” And the solution is then presented as part of the story (though not without a faint feeling of being judged).

I really liked this formalized style, which was both story and brain teaser. Having the sort of mathematically provable moment when it’s possible to solve the mystery was a great ego buster, too. He does play fair, but no fairer than he has to.

The Decagon House Murders saw another author taking a shot at the honkaku style, but using a style almost unbearably imitative of Agatha Christie, particularly of her most popular work, And Then There Were None. Personally I did not like that book, but it did break new ground (as Christie often did) and I understand its appeal. But here as there we have contrivance upon contrivance.

The main characters — all of whom refer to each other by the names of famous mystery novel writers because they’re in a book club together — travel to a remote island, the site of a horrible multiple murder, to stay in the famous ten-roomed house near the ruins of the original location. Needless to say murders start happening, while simultaneously a handful of others start trying to unravel the original mystery and this new one while stuck back on the mainland.

In some ways it’s a great little puzzle box, but in others it felt so contrived as to break the fair play limitations of honkaku. I won’t spoil it here (it’s still a fun, short read) but some of the choices in how the narrative is presented, the way the locations are laid out, and so on, seem to be solely in service to this specific plot. Like imagine if there was a secret knife holder right by the victim’s bed that only the murderer could use — that’s not playing fair! And so it seems occasionally with this one.

A more modern mystery that fits into the “social” genre Shimada wished so strongly to leave behind is The Devotion of Suspect X, by Keigo Higashino. This one, it is no spoiler to say, turns the mystery format back to front in the style of Columbo, beginning with the crime and its perpetrator, and progressing through the aftermath and subsequent investigation. I greatly enjoy Columbo, and this would have been an excellent episode.

Honestly, to say more would be a disservice to anyone interested. The characters, especially the physicist and the detective, are interesting and their actions and interactions unpredictable and engrossing. What’s especially good is how the book gets you to reevaluate the characters on a regular basis, their insight, what they’re willing or able to do, and so on. And the whole thing is quintessentially Japanese in a way that’s hard to describe without spoiling anything.

I’m curious after reading these to go back to some of the original honkakus and see how they stand up. Sadly not all the works of the Japanese greats have been translated into English, so as Shimada laments, some of the best mysteries from that era are inaccessible to readers like me. But this may be considered Japan’s “golden age” for mysteries, corresponding with Christie, Sayers, Carr and the like, so I’d like to give them a shot and find out if, as is often the case, the originals remain in some respects unsurpassed.

Adding to this post a few weeks later; I read The Inugami Curse, by Seishi Yokomizo, one of the authors recommended by Shimada. It did not disappoint, and I found it to be quite a page turner. I had an inkling of the “solution” but I certainly did not get it completely, though I have a feeling that if I’d plotted out everyone’s comings and goings on graph paper I might have found a pattern. I’ll definitely be reading some more from Yokomizo.