Literature which was considered shocking on its debut is but rarely shocking three hundred years later. The Monk is no exception (as opposed to, say, Fanny Hill), though it’s easy to see how in a time of great piety and fear of the church, a tale of this type might be both universally reviled and devoured.

There are a few stories loosely interwoven, all based in or around a convent and monastery in 18th-century Madrid. The primary story is of Ambrosio, a supremely virtuous monk who has never left the monastery since infancy. His bubble of sanctity is punctured by a young monk who (spoiler warning) reveals himself to be a woman, a beautiful woman at that, and what’s more, utterly dedicated to Ambrosio in every way. There are also the stories of Lorenzo, whose sister is trapped in the convent under the watch of an evil Abbess, and Don Raymond, who is in love with that sister, having met her in a series of adventures ranging from banditti ambush to ghostly possession. The three stories play themselves out, the characters occasionally encountering or indirectly affecting one another.

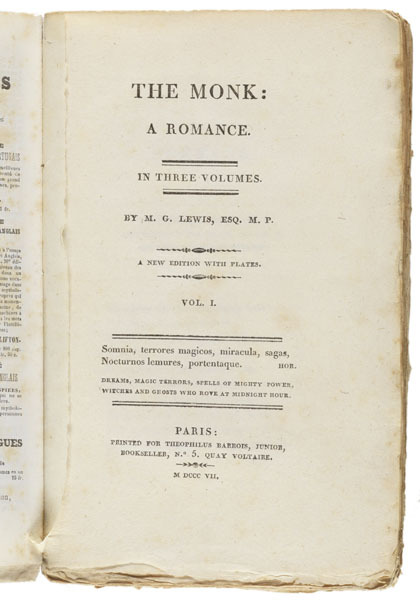

The Monk was written by a 20-year-old nobleman, and was instantly banned upon its release for being lewd and sacrilegious. And so it is: Ambrosio indulges in a laundry list of violent and carnal sins, all the while justifying it with a perverted religiosity, and the other religious figures are either evil and conniving or useless nonentities. There is frequent sexual violence, which is not to say (for the most part) rape, but a frank and unflinching treatment of the dark side of human sexuality, where it overlaps with other appetites and vices.

For all its worldliness, the book is clearly an amateur effort, though a largely successful one. Lewis was a talented writer (even his most vehement critics admitted so), and his style adapts equally well to the internal struggles of Ambrosio as to the romantic adventures of Don Raymond. Sentence by sentence Lewis is unimpeachable, and occasionally inspired (some of his poetry, inserted awkwardly into the narrative, is quite good), but the narrative barely hangs together and the characters seem arbitrarily motivated, traversing the book like wind-up toys. The pace is unsteady and the tone unregulated. The strength of expression and lack of structure remind me very much of another young author’s first novel: Fitzgerald’s excellent but lopsided This Side Of Paradise. Both are worth a read, though both are more enjoyable for the promises they make on their authors’ behalf.