When you are drowsy in a morning, and find a reluctance to getting out of your bed, make this reflection with yourself: ‘I must rise to discharge the duties incumbent on me as a man.’

‘And shall I do with reluctance what I was born to do, and what I came into the world to do?’ What! was I formed for no other purpose than to lie sunk in down, and indulge myself in a warm bed? —’But a warm bed is comfortable and pleasant,’ you will say. —Were you born then only to please yourself; and not for action, and the exertion of your faculties?

Do you not see the very shrubs, the sparrows, the ants, the spiders, and the bees, all busied, and in their several stations cooperating to adorn the system of the universe? And do you alone refuse to discharge the duties of man, instead of performing with alacrity the part allotted you by nature?

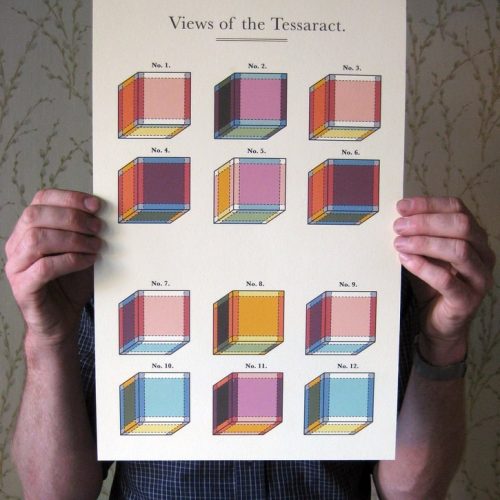

tesseract poster on etsy

Doubts About Lytro’s “Focus Later” Camera

The Brilliance of Dwarf Fortress

The Brilliance of Dwarf Fortress

An interesting New York Times article about the cult game Dwarf Fortress. It actually refers to a post I made on Metafilter several years ago about the game.

Fontanesi, “Quiete”

At The Close Of Every Day – “ All Things End In Waters”

The Silja Symphony

A calm and delicate song, with a lot of subtle craft in it that sets it apart from the herds of voice-and-acoustics out there. Reminds me of Damien Jurado, but I like this better. A bit of extra instrumentation and some unexpected minor harmonies make it less predictable than its unassuming strumming seems to imply at first.

The bold they kill, th’ unwary they surprise;

Who fights finds death, and death finds him who flies.

The Secret Agent (Joseph Conrad, 1907)

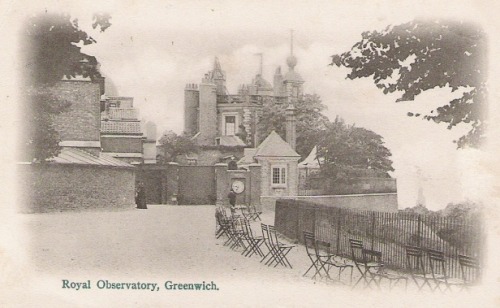

When you really come down to it, there really isn’t much to The Secret Agent, Conrad’s schizophrenic ensemble piece describing several “anarchists” in a sort of imagined historical account of the real Greenwich Observatory bombing of 1894. Yet its pages are rich and meticulously crafted, full of detail which could only be supplied by someone completely involved with his work. The framework of the novel, though, its “skeleton,” as Conrad refers to it in a conciliatory 1920 preface, is only the barest suggestion of a story. The title might lead you to think it’s a tale of espionage and high drama, but in fact it’s more of a progression of baroque character studies.

Conrad’s justification (for following reviews savaging the book for its supposed depravity and lack of any sort of real edification, he felt the need to append one) was simply that, having been told a few details of the bombing, he felt a set of characters and actions evolve in his head surrounding that “blood-stained inanity,” and simply set pen to paper. It was written quickly and fairly continuously, a fact that shows in the unvarying tone and inspired feel of the writing.

The perspective is one of omniscience, and Conrad puts his characters under the glass so minutely that pages and pages of description, narration, and thoughts will separate two lines of dialogue. It’s almost as if Conrad is narrating a film, and feels the need to stop it constantly in order to explain what you’ve missed. This applies to inconsequential events as well as serious ones: the detail with which the grotesque cab driver is rendered (a perfectly Dickensian caricature) is equal to that of the difference between the moral imperatives driving Chief Inspector Heat and the Assistant Commissioner. And while the former is certainly of a lesser fundamental weight than the latter, both are treated with the same slightly removed tone of levity that pervades the whole book. Conrad is a funny guy, it turns out, and though the events described might be of the most terrible import, they are all the same to our amused narrator.

It’s not a quick read, though it isn’t a particularly long book: my cheap Dover edition is around two hundred pages, and more normally-printed ones probably will reach three hundred or more. The subtitle for the book is “A Simple Tale,” and indeed the tale is simple, but the writing is dense and each sentence seems absolutely necessary. While in other books I can get away with accidentally skipping a sentence or two after looking away to pick up my coffee or what have you, in The Secret Agent I would immediately get lost. And yet so much of the book is completely irrelevant to every other part! Don’t ask me why it is this way, it just is.

The espionage and action in the book is so minimal that anyone looking for a thrill will be disappointed. The plot never takes off, but on the other hand, the plot is more of a red herring, a nail from which to hang the rest of the book. There’s a lot to like about The Secret Agent, but the independence of each enjoyable element robs it of profundity. That said, if you like the way Conrad writes in general — well, he wrote this.