I have yet to meet a single person who has heard of, much less read, Ten Thousand A-Year. Yet it was extremely popular in 1855, from which period much literature is generally remembered. It is a British legal drama-comedy concerning the rise and fall of one Tittlebat Titmouse, a miserably poor London dandy who lives in squalor but aspires to aristocracy, not to say gentility.

He comes unexpectedly into an enormous fortune after some legal hijinx displace the Aubreys, a placidly virtuous family occupying the country seat of Yatton. They are thrown down and he is elevated to wealth and popularity. As one might expect, the experience is edifying for the pious Aubreys and nearly fatal to the unprincipled Titmouse.

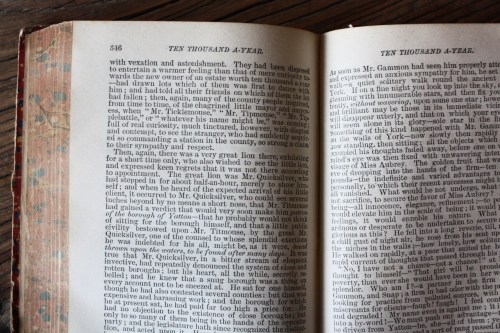

The book is quite long: nearly a thousand pages of very dense text (as you see), and encompassing several years of the characters’ lives. The farcical early life of Titmouse, the legal proceedings, a contested election in Yatton, and a huge amount of scheming, mannered dialogue, and much more all figure. Warren writes in a sort of unedited fashion, taking pages and pages to dilate on minor events or moralize (he was a preacher, and it shows); he has a decent style and an occasionally hilarious or remarkable turn of phrase, but it’s easy to tell when he is inspired and when he is simply getting through the story. Poe wrote in Blackwoods that it was “shamefully ill-written” and called the characters “stupid and beastly indecencies.” He was probably right; Warren is frequently sentimental and affected, and the absurd names of characters don’t help.

The book seems to set out with a different focus than the one it gradually acquires, which, in its defense, was probably a common occurrence in serial fiction of the sensational type. The readers are taught to sympathize with Titmouse, and Kate is set up early as a major character – but both are reduced to window dressing within a few hundred pages, ceasing to act and lacking any power to move the story.

In fact, with Titmouse being reduced to a mean-spirited sot and the Aubreys being tiresome in their virtue, the prime mover and chief villain, Mr. Gammon, essentially becomes the protagonist. Unlike the rest of the characters, who are merely described as being “of superior understanding” yet never show it, Gammon actually is superior to all around him, and manipulates them at will by every means at his disposal, from lying to perjury to blackmail. He is a consummate scoundrel, but he is also realistic and unique, and I found myself more interested in his next move than in the fates of the rest of the characters, mere pawns.

I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone who isn’t interested in this particular kind and style of book. It was a rewarding read and I am glad to have read it, but there are surely better examples of this genre, and hundreds of superior books from the era. That said, it was fascinating to get into the mindset of the average reader of the mid-19th century. It’s not all Dickens and Twain and Melville — Ten Thousand A-Year was the John Grisham or Tom Clancy paperback of its time, and was easy to appreciate as such.

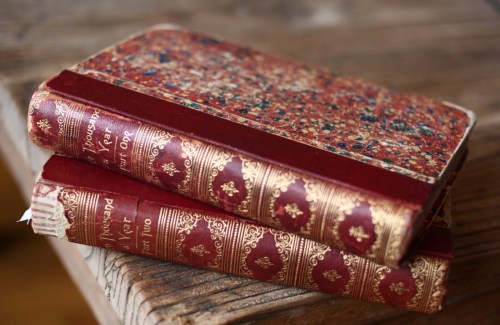

The edition I have (which has received more comments than probably any other book I own) is an undated Thomas Crowell & Co. printing, probably from the late 1840s or early 1850s. The binding is very fragile but remains bright, though the paper is of somewhat low quality and has darkened over time. The close-leaded type is unlike most I’ve seen, as the characters are fairly large but the spacing close enough to overlap. It was still easy to read, though Warren seems to have trouble dividing his writing into paragraphs, and there are occasional two-page spreads without a single break, giving the book a medieval air.

Postscript: this novel really is remarkable for the sheer number of characters, rivaling Dickens at his most indulgent, and while none approach the effortless characterization accomplished by that author, the cast of Ten Thousand A-Year is at least a memorable rabble. Here is a partial list, since if I don’t create one, it’s doubtful anyone else ever will:

Tittlebat Titmouse — destitute aspiring dandy

Charles Aubrey, Esq. — MP and occupant of the estate of Yatton, in Yorkshire

Agnes Aubrey — his wife

Miss Catherine Aubrey — his sister

Geoffry Delamere — young gentleman, in love with Kate Aubrey

Lord De La Zouch — Delamere’s father, a great lord, friend of Aubrey

Lady Stratton — wealthy aunt and helpmeet to the Aubreys

Lord Dreddlington — a proud and powerful noble, distantly related to Aubrey

Lady Cecilia Dreddlington — his daughter, eventually married off to Titmouse

Robert Huckaback — Titmouse’s colleague in poverty

Thomas Tag-Rag — Titmouse’s employer before his fortune

Oily Gammon — solicitor and chief schemer, in love with Kate Aubrey

Caleb Quirk — senior partner at Quirk, Gammon, and Snap

Messrs. Fussy Frankpledge, Mouldy Mortmain, Tresayle, Lynx, Subtle, Quicksilver — solicitors and counsel for the plaintiffs

Messrs. Runnington, Parkinson, Sterling, Crystal — solicitors and counsel for the defendants

Mrs Squallop — Titmouse’s landlady early on

Dr. Tatham — Parish priest of Yatton

Barnabas Bloodsuck, Cephas Woodlouse, Mr. Centipede, Mr. Going Gone — agitators and operators of the Yorkshire Stingo paper

Toady Hug, Alderman Addlehead, Mr. Viper, &c. — various self-interested gentlemen

Mr. Grasp, Mr. Grab — operators of a private debtor’s prisons

Mr. Pimp Yahoo, Mr. Algernon Fitz-Snooks, Sir Harkaway Rotgut Wildfire, &c. — hooligans and hangers-on of Titmouse

Mr. Venom Tuft — sycophantic socialite

Phelim O’Doodle — strategist for Titmouse in the Yatton election

Mr. Crafty — strategist for Delamere

Swindle O’Gibbet, Micah M’Squash, Mr. O’Shirtless, Mr. O’Toddy — Irish stereotypes

Dr. Diabolus Gander, Esq. — quack to the nobility

Duke of Tantallan — friend to Lord Dreddlington

Rev. Smirk Mudflint — leader of Yatton’s radical Unitarian church

Dr. Flare, Mr. Quod, Mr. Pounce — officers of the Ecclesiastical court