I admit it freely and without shame: I love magical schools. Hogwarts may be the best known, but it’s not the first, nor did it exhaust the theme. That said, such an institution is no guarantee of a good story. Having realized that over two years I’d read four books where a girl attends and learns the mysteries of a magical school, I thought I’d compare.

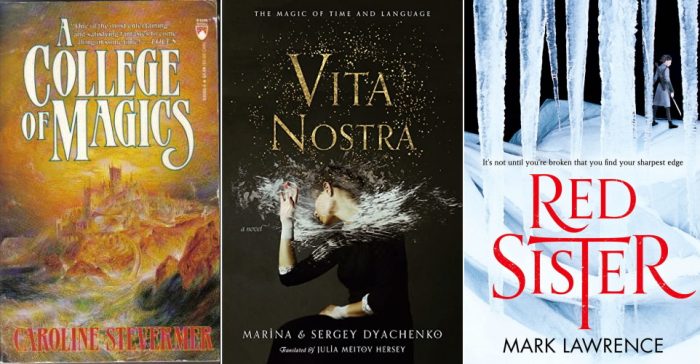

A College of Magics (Caroline Stevermer) is perhaps the most traditional of them, and having been released in 2002 during the height of Potterdom, it’s hard not to imagine there was a significant influence. But this book, which follows a young minor noble through her schooling at the eponymous college, leans far more toward the mystical or esoteric type of magic.

In Harry Potter, magic is practically machinery, able to be measured, taught, and its effects seen and understood, if never adequately explained (which complaint, made about children’s books, always makes me laugh). In Stevermer’s world, magic is much stranger and less predictable, a bit like in Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (which I suppose I should revisit).

The protagonist’s education and subsequent adventures are interesting but never wholly explicable, which ultimately robs the book of some of its power, as one often doesn’t really understand what’s going on or how something came about. I understand the value of holding back exposition, but the climax felt obscure, as though the author had something in mind but couldn’t figure out a way to express it.

Fortunately the writing moment by moment is sparkling, with remarkably funny dialogue and sharply drawn characters. I liked the book, but have hesitated to embark on the sequel because I’m worried it will again fail to offer the desired clarity.

In Vita Nostra (Marina and Sergey Dyachenko), however, lack of clarity is used to great advantage. For much of the book we are as in the dark as the main character, who is coerced into attending an extremely odd (and not necessarily in the quirky way) post-secondary school in rural Ukraine. Her puzzlement, but also her determination, is evident as every bizarre and trying situation presents itself. Why are the students forced to “read” books of seemingly random blocks of letters? Why does it make her sweat and lose time? What is driving the upperclassmen insane, and how can they drink boiling tea?

Unlike the other books on this list, in which the characters note their surroundings but don’t linger on them, the day-to-day difficulties are present in convincing detail in Vita Nostra. The miserable little town where the story takes place, the dilapidated Soviet buildings with their clanking pipes, the exasperating roommates, the obviously threadbare yet somehow obviously also important school itself – they all feel well realized and important. (Incidentally, the translation from the Ukrainian is excellent.)

It’s difficult to say much without spoilers, but I’ll venture to hint that the mysterious element that qualifies this story as belonging in this review is totally unique and very surprising. I thought Vita Nostra one of the most original books I’d read in some time, and I’ve recommended it widely — and it helps that it’s not part of a trilogy or more.

The Poppy War (R.F. Kuang) was unfortunately a disappointment. After a very promising start the book seemed to settle quickly into a “reluctant chosen one” arc, and things escalated so quickly that there was no impact when people started dying left and right. Assembling a sort of short-lived super-team didn’t add much excitement, and the explosive climax seemed unearned and somehow pointless. The idea of magical warfare in a gritty wuxia setting seemed like a home run, but ultimately the parts of this book I liked were few and far between.

Surpassing my expectations, on the other hand, Red Sister (Mark Lawrence) is the rare book that hit every note it tried to, kept me guessing and turning pages, and wrapped up leaving me wanting more.

Or perhaps the prologue set the bar so incredibly low that it had nowhere to go but up:

‘Thorn rolled her shoulders beneath black skin armour. She tightened the fingers of each hand around the sharp weight of a throwing star, her breathing calm, heart racing. “In this place dead watch me,” she breathed.’

Oh, how dreadful! I very nearly put the book down right then, after those two sentences. But I’m glad I didn’t.

Nona is a girl — not quite an orphan — who has been sold to a child merchant, and from him to a nunnery that trains assassins. Believe me, I was skeptical too for the first few pages. But Lawrence makes this story succeed not because assassin nuns are cool and have throwing stars — in fact it’s in spite of the fact that really, they aren’t.

The setting and the rules that govern it are entirely unknown to the ignorant, young Nona, and the reader learns along with her quite naturally about the state of the world and its fantasy-adjacent races and nations. What might have fallen flat done as an ordinary fantasy story, however, is made mysterious and enticing by hints at a sci-fi deep-time justification for it all that’s revealed refreshingly gradually and subtly (shades of the excellent Steerswoman series).

That all of humanity lives in a narrow band of thaw at the equator of an ice-covered planet, kept warm by an artificial moon focusing the light of a dying sun on it is clear within the first few chapters, yet this isn’t played up as some big mystery, in fact it’s commonplace knowledge no one seems to care or question in the least. The source of magic beneath the convent is called a “shipheart” and clearly not of this world. Ruins lie beneath the ice but “the missing” who occupied them are long gone. What the hell is going on?

Meanwhile more ordinary events and excitements befall Nona, who grows, makes friends, stumbles, fails, succeeds, and investigates, everything she does further illuminating the setting and the hidden threads of the plot. The book was so expertly paced that I challenged myself to read it without checking how much was left (on an e-reader), not wanting to be misled by page counts. It was at its worst — bad, frankly — when attempting to drum up drama rather than letting it emerge on its own, as the prologue and some other flashbacks demonstrated.

The slightly abrupt ending, leaving many things only hinted at or teased, didn’t frustrate me — in fact, I would have (like in Poppy War or many another first-of-three) been disappointed to have the limits of the world fully explored, rather than only suggested, so early in the story. As it was I simply wanted to immediately start reading the next installment.

One book I began but couldn’t seem to make any progress in, but would have fit in this list if I did, was The Priory of the Orange Tree. I found what bothered me about this one was that, like so many books in the fantasy genre, something is described as rare or extraordinary, but then we see it right away. I felt like the author showed their hand too early as a sort of amuse-bouche for readers who can’t be bothered to wait until later for the dragons and magical showdowns. What is there to look forward to, then? As Patrick Stewart once said, “I’ve seen everything.”

The escapist fantasy of a magical school insulated from the world is, I suppose, one of my ways of coping with the pandemic. In an era of virulent irrationality such as this, who wouldn’t want to go to a place where the rules governing us all are suspended, anything is possible, and there’s a reason for everything?