There are surely other worlds than this: other thoughts than the thoughts of the multitude, other speculations than the speculations of the sophist. Who then shall call thy conduct into question? who blame thee for thy visionary hours, or denounce those occupations as a wasting away of life, which were but the overflowings of thine everlasting energies?

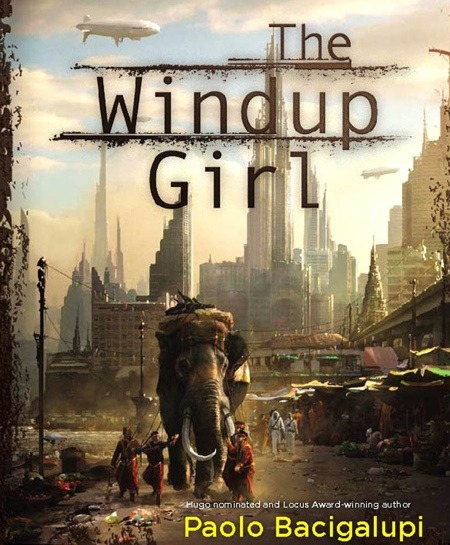

The Windup Girl (Paolo Bacigalupi, 2009)

The Wind-Up Girl came highly recommended by my family, and of course the usual breathless praise from within the sci-fi community made it out to be nothing less than a Neuromancer for this modern age. Biopunk, a dystopian future made from only the freshest fears of the present. It partially delivers on this promise, but also fails in the ways modern books I’ve read recently tend to fail.

The premise is certainly the best part of the book. Some distance into the future, perhaps a hundred years or so, bioengineered crops and organisms have supplanted natural ones, giving rise to new plagues and food shortages — not to mention a rising sea due (I assume) to global warming. The result is the “Contraction,” a reversal of the “Expansion” era of our day. Fuel and power are precious and the universally acknowledged currency is calories. The story takes place in Krung Thep, AKA Bangkok, in Thailand, where the Thai have maintained independence by ingenuity, independence, and grit. And, as a new and disease-resistant fruit introduced at the outset suggests, a seedbank and skilled bioengineers.

Unfortunately, the book never really delivers on its promises. The landscape is foreign in a way, but also filled with the lazy analogues endemic to modern sci-fi. The “kink-springs,” for instance, are nothing more than batteries, no matter how named. The privations of the Contraction are no barrier to most of the characters, poverty and heat seeming to be the main difficulties — whenever a “rule” of the new world is inconvenient, it is discarded, and guns, cars, and other things that should be impossible in this new world regularly appear; one is not convinced of their rarity simply by the characters gasping at their appearance. And the story itself is easily abstractable from the world; the Environment Ministry (the “White Shirts”) and Trade Ministry could just as easily be Pepsico and Coca-Cola, or Boeing and Northrup Grumman, since the conflict is more or less political. That’s where the book fails: despite the well-conceived backdrop, very seldom in The Wind-Up Girl (an almost peripheral character, incidentally) does anything happen that couldn’t happen in any other book or world. In the end, the meat and potatoes are generic thriller, and the bioengineering and global cataclysm are simply sauce.

The writing is also spotty. Like so many modern books, whatever isn’t a labor of love (often the premise and a couple inspired characters or situations) is filler, and you can tell when Bacigalupi is writing something he doesn’t particularly care about. There are a few nice turns of phrase here and there, and the beginning hints at a fragmented timeline that is abandoned shortly. He lacks variety in his phraseology as well (towards the end of the book, during a firefight, I read the word “chatters” at least six or seven times in the space of a few pages), and the dialogue is totally undifferentiated. Every character speaks in the same voice, though their internal narration is better.

Bacigalupi has written several other stories that take place in this world, and it seems to me that his great accomplishment was painting the background, but he has yet to actually produce anything but sketches in the foreground. For world-building, he gets a gold star, but for storytelling, no credit. Other modern sci-fi I’ve read has the same prose shortcomings, but in the Virga trilogy (and even in Mainspring, an inferior book by far) the story was unique to the situation. Not so here.

As for the herd of mankind, he [i.e. the rational man] is too well acquainted with their conduct with their conduct both in private and in public; their infamous connections, the dissipation of their days and the revels of their nights. He cannot therefore be very ambitious of the praise or approbation of such capricious people, who are often at a loss to please themselves.

Anatomia Vegetal (Bibliodyssey)

Out of nothing, nothing can be brought;

And that which is, can ne’er be turned to naught.

Giorgio de Chirico, The Tower (Tarot)

Because when you think about it, this is how it really is.

Extracts from Vanbrugh’s “The Provok’d Wife”

Const.: But she’s cold, my Friend, still cold as the Northern Star.

Const.: But she’s cold, my Friend, still cold as the Northern Star.Heart.: So are all Women by Nature, which makes ‘em so willing to be warm’d.

Const.: O don’t prophane the Sex; prithee think ’em all Angels for her sake, for she’s virtuous, even to a fault.

Heart.: A Lover’s Head is a good accountable thing truly; he adores his Mistress for being virtuous, and yet is very angry with her, because she won’t be lewd.

Heart.: Yet not one kind Glance in Two Years, is somewhat strange.

Const.: Not strange at all; she don’t like you, that’s all the business.

Const.: Ha, Heartfree: Thou has done me Noble Service in pratling to the young Gentlewoman without there; come to my Arms, Thou Venerable Bawd, and let me squeeze thee as a new pair of stays do’s a Fat Country Girl, when she’s carry’d to Court to stand for a Maid of Honour.

Const.: How now, Heartfree? What makes you up and Dress’d so soon? I thought none but Lovers quarrell’d with their Bed.

Heart.: Prithee take heart, I have great hopes for you, and since I can’t bring you quite off of her, I’ll endeavour to bring you quite on; for a whining lover, is the damn’d’st Companion upon Earth.

Const.: So, Play-fellow: Here’s something to stay your Stomach, till your Mistress’s Dish is ready for you.

Heart.: Some of our old Batter’d Acquaintance.

Heart.: But Prithee advise me in this good and Evil, this Life and Death, this Blessing and Cursing, that is set before me. Shall I marry — or die a Maid?

Const.: Why Faith, Heartfree, Matrimony is like an Army going to engage. Love’s the forlorn Hope, which is soon cut off; the Marriage-Knot is the main Body, which may stand Buff a long, long time; and Repentance is the Rear-Guard, which rarely gives ground as long as the main Battle has a Being.

Heart.: Conclusion then; you advise me to whore on, as you do.

Const.: What say’st thou, Friend, to this Matrimonial Remedy?

Heart.: Why I say, it’s worse than the disease.

Const.: Here’s a Fellow for you: There’s Beauty and Money on her Side, and Love up to the ears on his; and yet—

Heart.: And yet, I think, I may reasonably be allow’d to boggle at marrying the Niece, in the very Moment that you are debauching the Aunt.

Const.: Why truly, there may be something in that.

Lady Fancyfull, Lady Brute, and Bellinda Lady F.: Lord, how proud some would some poor Creatures be of such a Conquest? But I alas, don’t know how to receive as a favour, what I take to be so infinitely my due. But what shall I do to new mould him, Madamoiselle? for till then he’s my utter aversion.

Lady F.: Lord, how proud some would some poor Creatures be of such a Conquest? But I alas, don’t know how to receive as a favour, what I take to be so infinitely my due. But what shall I do to new mould him, Madamoiselle? for till then he’s my utter aversion.

Lady B.: Shield me, kind Heaven, what an inundation of Impertinence is here coming upon us!

Bellinda: Well, you Men are unaccountable things, mad till you have your Mistresses; and then stark mad till you are rid of ’em again. Tell me, honestly, is not your Patience put to a much severer Tryal after Possession, than before?

Lady B.: But after all, ’tis a Vicious practice in us, to give the least encouragement but where we design to come to a Conclusion. For ’tis an unreasonable thing, to engage a Man in a Disease which we before-hand resolve we never will apply a Cure to.

Bellinda: ‘Tis true; but then a Woman must abandon one of the supreme Blessings of her Life. For I am fully convinc’d, no Man has half that pleasure in possessing a Mistress, as a Woman has in jilting a Gallant.

Sir John Brute Sir John: Best Wives! —the Woman’s well enough; she has no Vice that I know of, but she’s a Wife, and— damn a Wife; if I were married to a Hogshead of Claret, Matrimony would make me hate it.

Sir John: Best Wives! —the Woman’s well enough; she has no Vice that I know of, but she’s a Wife, and— damn a Wife; if I were married to a Hogshead of Claret, Matrimony would make me hate it.

Sir John: Oons, Sir, I think a Woman and a Secret, are the two Impertinentest Themes in the Universe. Therefore pray let’s hear no more, of my Wife nor your Mistress. Damn ’em both with all my Heart, and every thing else that Daggles a Petticoat, except four Generous Whores, with Betty Sands at the head of ’em, who were drunk with my Lord Rake and I, ten times in a Fortnight.

Constable: Come Sir, out of Respect to your Calling, I shan’t put you in the Round-house; but we must Secure you in our Drawing-Room till Morning, that you may do no Mischief. So, Come along.

Sir John: You may put me where you will, Sirrah, now you have overcome, me — But if I can’t do Mischief, I’ll think of Mischief — in spite of your Teeth, you Dog you.

Sir John: And now, what shall I do with her? —If I put my Horns in my Pocket, she’ll grow Insolent. — If I don’t, that Goat there, that Stallion, is ready to whip me through the Guts. —The Debate then is reduc’d to this: Shall I die a Hero? or live a Rascal? —Why, Wiser Men than I have long since concluded, that a living Dog is better than a dead Lion.

Sir John: Sure if Woman had been ready created, the Devil, instead of being kick’d down into hell, had been Married.