drugget: a coarse, shabby fabric of cotton or wool (from the French drogue, trash)

murrain: a plague, especially among cattle (from the French moraine, pestilence)

gymnosophist: one of a sect of Indian ascetics who refused themselves clothes

prorogue: to postpone, discontinue, or suspend a legal or legislative meeting

cruet: one or more small bottles or containers for oil, vinegar, salt, etc

fadge: to agree or succeed; or, a bale of wool under 100kg

epopee: an epic poem, or epic poetry in general

spilth: something that was spilled (clearly)

nanger: apparently a type of gazelle?

tomrig: a wild girl or tomboy

fumid: smoky or vaporous

froppish: testy or contrary

diffide: to act distrustfully

peckled: speckled

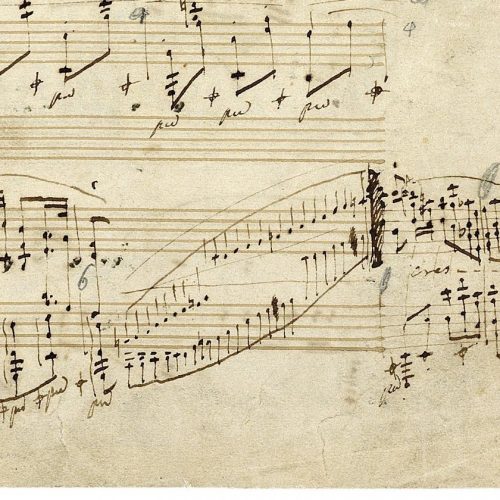

End of Chopin’s original of the Polonaise in A flat (Op. 53) (I love how he extended the bars)

Chopin – Piano Sonata No.2 (Op. 35) (Grave – Doppio movimento)

Another beautiful, breezy, endlessly surprising piano piece. I don’t know who’s playing, but from the powerful expression I’d guess it’s Horowitz. The variability seems almost improvisational, but it rewards repeated listening with wonderful motifs. But listening too closely to Chopin is like studying butterflies.

For, impartially speaking, the French are as much better critics than the English, as they are worse poets. Thus we generally allow that they better understand the management of a war than our islanders; but we know we are superior to them in the day of battle. They value themselves on their generals, we on our soldiers. But this is not the proper place to decide that question, if they make it one.

Horner: Doctor, there are quacks in love as well as physic, who get but the fewer and worse patients for their boasting; a good name is seldom got by giving it one’s self; and women, no more than honour, are compassed by bragging. Come, come, Doctor, the wisest lawyer never discovers the merits of his cause till the trial; the wealthiest man conceals his riches, and the cunning gamester his play. Shy huspands and keepers, like old rooks, are not to be cheated by a new unpractised trick: false friendship will pass now no more than false dice upon ‘em; no, not in the city.

It’s like Big Loader, Mouse Trap, Rube Goldberg, and Japan had a megababy. (HD)

Animal Collective – “In The Flowers”

Merriweather Post Pavilion

So the last thing I listened to from Animal Collective was Here Comes The Indian from 2003. Then I keep hearing about this album and the guys’ side projects and think well, what’s the harm in giving it a listen. Why didn’t anybody (other than practically every music blog and magazine) tell me it was this good? I’m very disappointed that I can’t walk down the street without being earpunched by the same goddamn Kesha song for a year straight, but somehow I haven’t accidentally heard a single Animal Collective song since I was in college. Crazy cover art here.

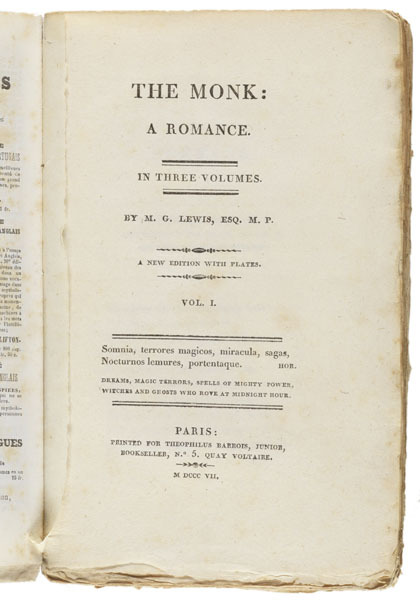

The Monk (Matthew Lewis, 1796)

Literature which was considered shocking on its debut is but rarely shocking three hundred years later. The Monk is no exception (as opposed to, say, Fanny Hill), though it’s easy to see how in a time of great piety and fear of the church, a tale of this type might be both universally reviled and devoured.

There are a few stories loosely interwoven, all based in or around a convent and monastery in 18th-century Madrid. The primary story is of Ambrosio, a supremely virtuous monk who has never left the monastery since infancy. His bubble of sanctity is punctured by a young monk who (spoiler warning) reveals himself to be a woman, a beautiful woman at that, and what’s more, utterly dedicated to Ambrosio in every way. There are also the stories of Lorenzo, whose sister is trapped in the convent under the watch of an evil Abbess, and Don Raymond, who is in love with that sister, having met her in a series of adventures ranging from banditti ambush to ghostly possession. The three stories play themselves out, the characters occasionally encountering or indirectly affecting one another.

The Monk was written by a 20-year-old nobleman, and was instantly banned upon its release for being lewd and sacrilegious. And so it is: Ambrosio indulges in a laundry list of violent and carnal sins, all the while justifying it with a perverted religiosity, and the other religious figures are either evil and conniving or useless nonentities. There is frequent sexual violence, which is not to say (for the most part) rape, but a frank and unflinching treatment of the dark side of human sexuality, where it overlaps with other appetites and vices.

For all its worldliness, the book is clearly an amateur effort, though a largely successful one. Lewis was a talented writer (even his most vehement critics admitted so), and his style adapts equally well to the internal struggles of Ambrosio as to the romantic adventures of Don Raymond. Sentence by sentence Lewis is unimpeachable, and occasionally inspired (some of his poetry, inserted awkwardly into the narrative, is quite good), but the narrative barely hangs together and the characters seem arbitrarily motivated, traversing the book like wind-up toys. The pace is unsteady and the tone unregulated. The strength of expression and lack of structure remind me very much of another young author’s first novel: Fitzgerald’s excellent but lopsided This Side Of Paradise. Both are worth a read, though both are more enjoyable for the promises they make on their authors’ behalf.