mandrel: the bar or cylinder on which a spinning tool or workpiece (e.g. a millstone) is mounted

gabion: wicker baskets or steel drums filled with rocks and used in fortification or construction

palingenesis: rebirth or baptism; in biology, embryonic forms revisiting evolutionary history

maquis: a scrubby Mediterranean plant; also, a French resistance group in World War II

ergastulum: a subterranean prison or dungeon in which dangerous slaves were kept

fytte: archaic spelling of fit, in this case meaning a section of a poem or ballad

prorogue: to defer or postpone, especially in legislative bodies

encaustic: art formed or fixed by a burning or heating process

swivet: a state of nervous excitement, confusion, or anxiety

haruspex: one who divines the future by observing entrails

brontoscopy: divination through the sound of thunder

febrifuge: a drug or drink for reducing fever

dubitation: archaic term for doubt

ferine: alternative spelling of feral

kyst: a chest or container

Opening shot of “Zatoichi’s Flashing Sword” (1964)

The Drones – “I See Seaweed”

I See Seaweed

The truth is I can’t stand the way this guy sings, but he is one of the rare songwriters out there who can make up for a mouthful of marbles with the quality of his writing. Wait Long By The River… had surprising lyrical depth, and I See Seaweed, the title track in particular, does as well — juxtaposing rising sea levels with more personal human iniquities. It’s not happy music, however, so if you’re looking for something to drag you out of the ditch, this ain’t it. (buy at band website)

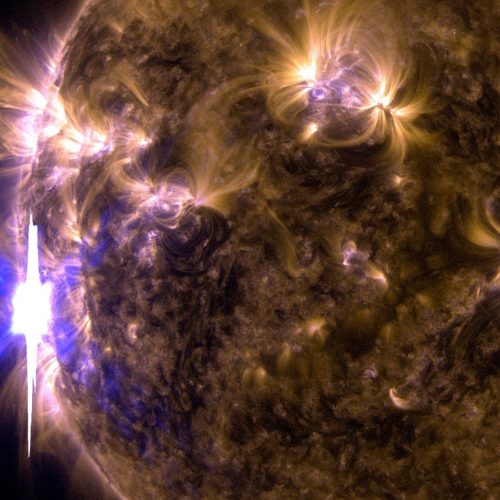

An enormous flare maxing out the Solar Dynamics Observatory’s sensors, above, and split into different wavelengths, below

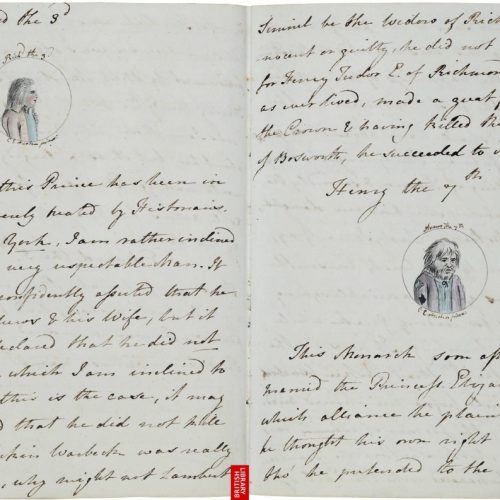

15-year-old Jane Austen’s parodical history of England

“During his reign, Lord Cobham was burnt alive, but I forget what for.”

“It was in this reign that Joan of Arc lived & made such a row among the English. They should not have burnt her – but they did.”

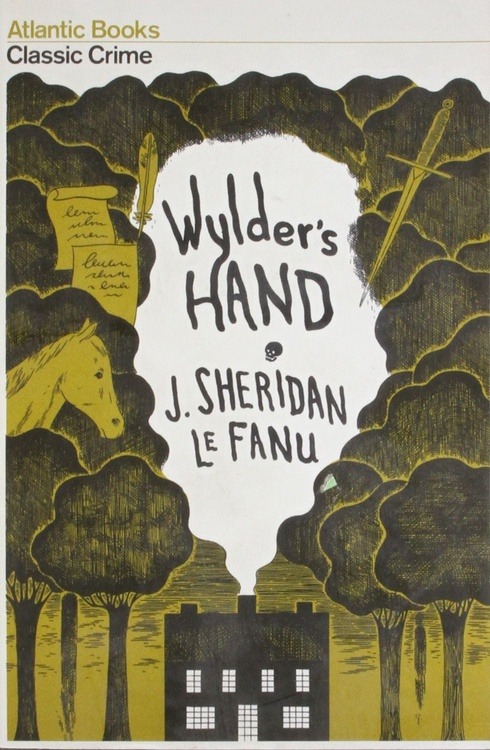

Wylder’s Hand (J. Sheridan Le Fanu, 1864)

This pastoral mystery is one of the less-read works of the prolific and (then) popular Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. In the true Le Fanu style, there is an abundance of natural beauty, a pervasive sense of foreboding, and a deep mystery with an air of the supernatural.

Charles de Cresseron, our narrator, is visiting the town in which he grew up to advise on the estate issues of an old acquaintance, and shortly becomes peripherally involved with mysterious happenings surrounding the intertwined and feuding families of the Lakes, the Wylders, and the Brandons. It’s a fun and interesting book, yet with much to criticize.

Vocabulary: Perpetual Pebble Edition

psephology: the study of elections (from psephos, pebble, once used to vote in Greece)

hobbledehoy: a clumsy, awkward youth (one literal etymology yields “hedge-goblin”)

pelmet: ornamentation over windows or doors to conceal curtain fastenings

compony : in heraldry, alternating squares of color and metal (also gobony)

anteambulo: one who walks before an important person to clear the way

gamboge: strong yellow pigment, made from a resin used as a purgative

Cencian: patricidal or fratricidal, after an infamous Italian noblewoman

manumission: the act of freeing a slave, or the state of a slave freed

tufa: porous limestone usually deposited by mineral-rich streams

exuviae: cast-off parts, skins, or moltings, such as shells or wings

ormolu: alloys made to imitate gold on jewlery and decorations

consol: a type of government bond yielding perpetual interest

curule: of the highest rank (occupier of the eponymous chair)

claque: sycophants, or hired applause (fr. claquer, to clap)

meteoria: ancient roman term for scatter-brainedness

jorum: a large bowl or vessel, or its contents

tenebrous: dark or gloomy (also tenebrose)

persiflage: light banter, or a frivolous style

raddled: interwoven or wattled; unkempt

paletot: a loose outer garment

The Twelve Caesars (Suetonius, 121 AD)

Creasy wrote in his Battles that the obscure machinations of warring east Asia “appear before us through the twilight of primaeval history, dim and indistinct, but massive and majestic, like mountains in the early dawn.” So one would expect the lives of such rulers as the Caesars to exhibit likewise such mythical prominence. But the stories provided by Suetonius, while they must be read with a skeptical eye now and then, feel too minutely detailed, too personal and arbitrary, to be anything but truth. It’s a mountain of anecdote and hearsay, so as history it is somewhat unreliable, but it’s as vivid a collection of character portraits as has ever been assembled.