The Gygerkarte, or Gyger Map (and detail), made in 1667 by Hans Conrad Gyger and one of the first ever to represent a landscape in this intricate and accurate fashion.

The Gygerkarte, or Gyger Map (and detail), made in 1667 by Hans Conrad Gyger and one of the first ever to represent a landscape in this intricate and accurate fashion.

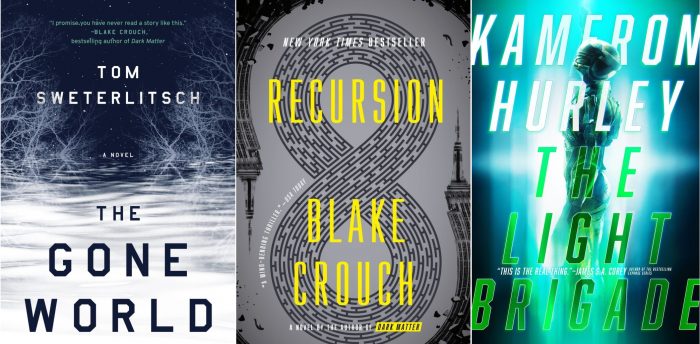

I’ve found that when it comes to science fiction, I have a soft spot for time travel. Although the concept is, of course, fundamentally hokey, I enjoy a clever take on it that subverts your expectations about what the causes or consequences of it could be. These three novels, all released in the last two years, achieve that with varying levels of success — but still have trouble tying up every loose end, which really is the duty undertaken by a novelist undertaking an intricately plotted mind-bender.

I read them in the order listed, and of the three, I think The Gone World is the best of them, with Recursion a close second, and The Light Brigade trailing rather far behind them. I’ll try to avoid major spoilers, but part of the trouble of each is its ending, so I must speak in general terms about that.

Read more

Athanasius Kircher welcomes guests to the Collegio Romano. Kircher speculated in his time that “plague in general is a living thing,” as this Public Domain Review piece explains.

Goldmund – “Grass Rides”

Famous Places

Goldmund’s melancholy, barely-there compositions make excellent background music, but occasionally one emerges with a clarity of theme that demands attention. This one reminds me of Hauschka’s “Paige and Jane.” (bandcamp)

talapoins: small African monkey with olive fur and webbed hands; or in Thailand, a monk

santon: a certain type of Muslim monk or hermit, sometimes regarded as akin to a saint

calcine: to heat a metal and achieve reduction or drying, often leaving a residue, calx

wenny neck: having or resembling a fatty cyst (wen); or, an overcrowded large city

antimacassar: protective covering for the top or back of upholstered furniture

parterre: patterned flower garden; or rear, ground-level seats in a theater

brickbat: piece of brick used as a weapon; or, a blunt criticism or remark

macadamize: to pave using broken stone (macadam) and asphalt or tar

palempore: Indian bed covering or cloth, often with a flower pattern

aigrets: ornament made of or resembling a plume (i.e. of an egret)

tamarisk: shrub with small leaves and light pink flowers

serail: women’s living quarters in old Islamic society

tecthtrevan: mobile throne reserved for royalty

rede: advice or interpretation (or to provide it)

apricate: to sunbathe or expose to sunlight

giaour: derogatory term for a non-Muslim

mulct: to obtain by fraud; or, a small fine

sea fencibles: defensive naval units

tarradiddle: a trivial falsehood

dwimmer: illusion or magic

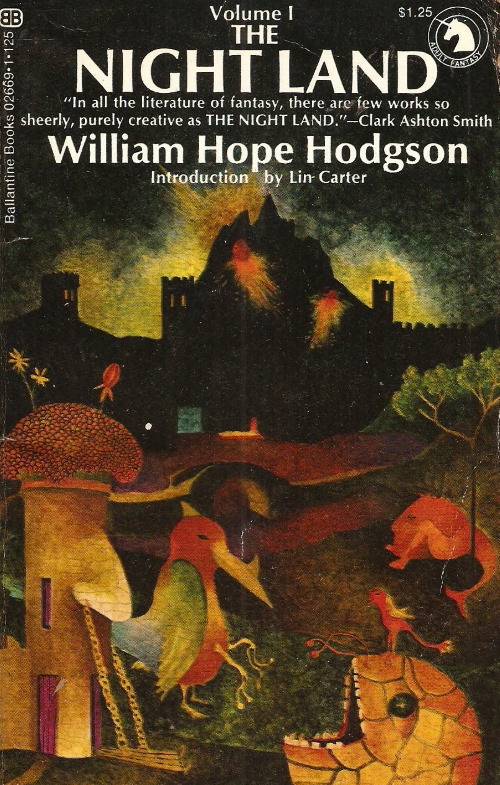

The Night Land is an astonishingly original, imaginative, and bizarre piece of fiction — one of the most memorable books I’ve ever read. And yet, so powerful are its idiosyncrasies that I would hesitate to recommend it to anyone.

Hodgson was among the progenitors of what was called for some time “Weird fiction,” an ur-genre which translated to modern parlance comprises horror, science fiction, fantasy, and others not common at the time, though with serious literary pretensions, to differentiate it from the lurid and numerous stories and novellas appearing in pulp magazines.

He is best known today for a few of his stories of nautical horror (“The Voice in the Dark” and “The Derelict” for instance) and the genre-flouting The House on the Borderlands, whose divagations in deep time and space place it in a lonely hinterland halfway between supernatural horror and a long-form narrative of a DMT episode.

The Night Land inhabits a similarly unusual conceptual Venn diagram: A three-way combination of historical epic, hard sci-fi, and travel diary. The final product is more than the sum of its parts, and deserves to be numbered among the founding documents of science fiction — yet Hodgson’s styling and narrative choices are so frustrating that I sometimes wished I could imitate the protagonist and project my own soul forward in time so as to escape his unceasing exposition.

The book begins with a framing story of the protagonist, who remains nameless throughout the hundreds of pages. He is a strong young man of the 17th century who falls in love with a woman who, he finds, experiences eerily similar dreams of a strange world where it is always night. Soon the narrator finds himself in that world, laboriously explaining the apparent coexistence of his soul and mind in both worlds with the passion of one describing a religious experience.

Read moreI now rambled about in great uneasiness from the coffee-house to the promenade, from thence to the museum, from the museum to the tavern, from the tavern to the exhibition of wild beasts, and at last to the playhouse, but I could nowhere find tranquillity.

Lawrence Flammenberg, The Necromancer; or, The Tale of the Black Forest

Angel Olsen – “Lark”

All Mirrors

One of the best album openers I’ve heard in some time, “Lark” puts Olsen’s almost Parton-esque crooning in juxtaposition with orchestral strains, backed by pulse-like percussion that promises a heart attack and delivers one about a minute in. (artist website)

A soothing demonstration of fluid dynamics from Cambridge (link)